Rice farmer Carlito “Ka Carling” Castro dreads the upcoming harvest season. With high prices of farming inputs, coupled with dropping prices of palay or unhusked rice, the 65-year-old farmer from Guimba, Nueva Ecija expects, at most, to just recover the cost of production.

For farmers who grow the staple that feeds 110 million Filipinos, laboring just to break even is already good news. Ka Carling has little hope for net profits to support his health expenses, he told Rappler in an interview.

Ka Carling strives to continue farming even after being diagnosed with a heart condition. He said this is the only source of income for his family.

A widower, Ka Carling currently lives with the family of his youngest child. While his income from planting rice suffices for their everyday food, the Guimba farmer does not know where to get funds for his medication and some medical procedures he needs to undergo.

“Base ho sa findings ng doktor, lumalaki raw ang puso ko. Nitong huling check-up, eh kailangan daw ho i-angiogram ako, doon nila makikita raw kung may bara ‘yung mga ugat,” he said.

(Based on my doctor’s findings, my heart enlarges. During my last medical check-up, the doctor said I need to undergo an angiogram, so they can see if there are any blockages in my veins.)

An angiogram is a medical X-ray procedure meant to look at the blood vessels in one’s body, and check for arterial blockages. This costs P50,000 to P60,000.

“Pagka mayroon daw nakitang bara, bawat isa ay nasa P100,000 daw ‘yung ihahahanda ko. Eh sa ngayon po gamot pa lang ang mayroon ako,” he added.

(If they saw blockages, I was told the removal of each would cost P100,000. But right now what I have are only medicines to keep me going.)

Doctors, however, have warned him that taking medication does not guarantee a cure and urged him to undergo angiogram tests. Ka Carling spends at least P10,000 monthly for his medicines.

“Eh kino-compute ko nga ho, kung i-e-estimate ko itong aanihin ko pa lang, hindi ko ho talaga makakayanan kasi may babayaran ako sa bangko na P100,000 ‘yung inutang ko roon,” he said.

(I was computing, if I would estimate my earning from what I will harvest, it’s really not enough because P100,000 would already go to paying my bank loan.)

Like most Filipino farmers, Ka Carling also loans money either from the bank or from private individuals to fund farm inputs during the planting season, and pays upon harvesting.

Skyrocketing prices of farm inputs

Ka Carling told Rappler that for farmers who loan capital, the skyrocketing prices of fertilizer are a huge burden.

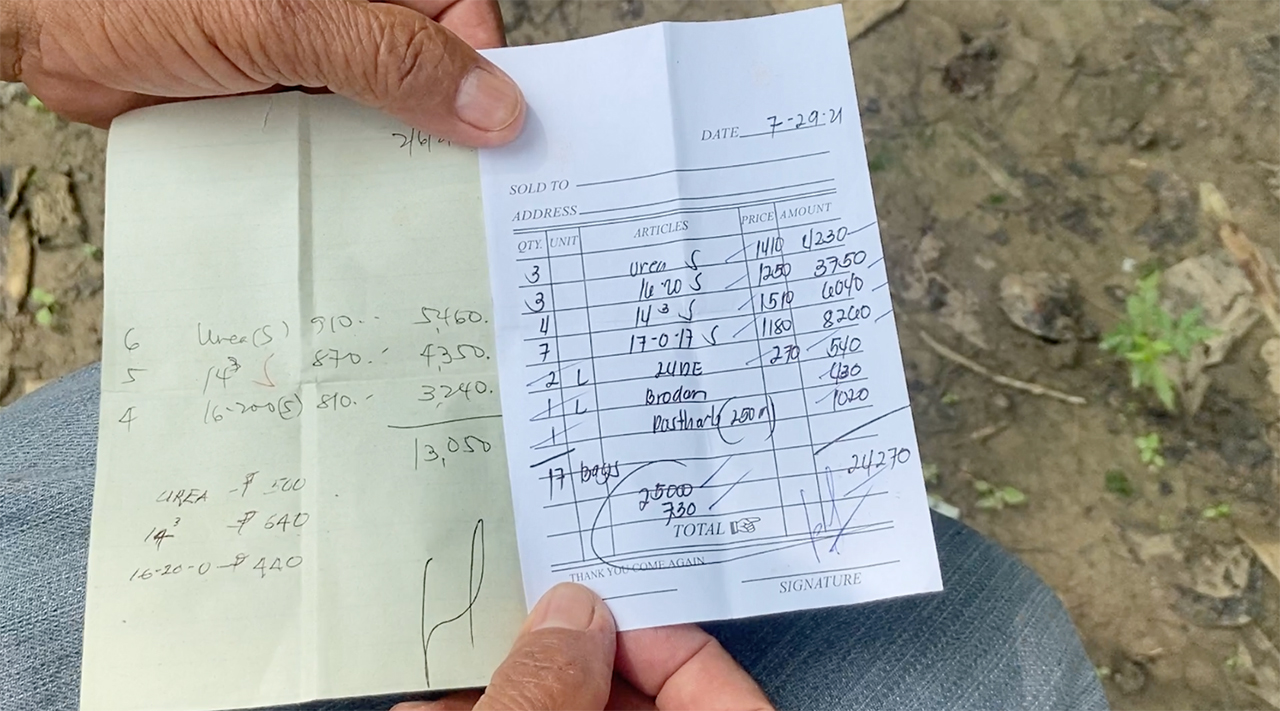

Comparing receipts dated February 6, 2021 and July 29, 2021, he said the price of Urea went up by P500 per 50-kilogram bag. The price of Triple 14 – the complete fertilizer with equal percentages of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium – increased by P640 per bag, while the 1620-0, or ammonium phosphate, went up by P440 per bag.

The rice farmer used approximately 18 bags of mixed fertilizers for his 1.7-hectare farm land in the last farming season. While he cannot really say the total amount he spent, Ka Carling said it’s almost impossible to recover the money spent on fertilizer from what he expects to earn this October.

He lamented the price hike, saying it was unjust and that it’s still puzzling why it had to rise that much. He complained that even when fertilizer prices rise, the farmgate price of palay remains low.

“Apart from the high cost of farm inputs such as fertilizer, pesticides, and farm workers’ salary, we face the burden, when the harvest season comes, of selling our produce based only on how much the buyer is willing to pay. And it’s currently low,” he said in Filipino.

During the main crop season in 2020, Ka Carling was able to sell his palay produce at P15 to P16 per kilogram (/kg) – rates much lower compared to the P20 to P22/kg before the pandemic. He said he expects to get the same rate this year.

The government, through the Fertilizer and Pesticide Authority (FPA), explained that fertilizer prices hiked globally as a result of increasing demand for them in other countries like India and Australia. It noted that India had already made an advance booking of 1.8 million metric tons of urea, while Australia increased its agricultural production, translating to greater consumption of fertilizers. The FPA also cited an increase in input cost as another factor for higher prices of fertilizer.

But Ka Carling said the government could have assisted the farmers given the sharp increase in fertilizer prices.

From breaking even to no income

The ailing Ka Carling expects to harvest an estimated 120 sacks of palay from his 1.7-hectare rice land. The Guimba farmer said he might only just recover the production cost, with nothing left for his medical needs.

“Kung matsambahan mo ‘yung presyo, baka labas-gastos ka lang. ‘Pag nakatsamba ka naman ng pagtaas, puwedeng ‘yun ang kita mo. Sa mga presyo natin ngayon, halos tabla-tabla lang kami. Kung mayroon mang maiwan, ‘yung pangkain,” he said. (If you’re lucky, you may just earn what you spent. If you chance upon an increase in price, that can be your income. But with our current prices, it’s almost breakeven. If there’s anything left, that’s for everyday food.)

Agriculture Undersecretary Ariel Cayanan said on September 21, that as of the second week of September, the farmgate price of dry palay in Nueva Ecija was at about P18/kg.

However, Ka Carling said fellow Guimba farmers were only able to sell their dry palay at P14/kg while some farmers in Baloc, Santo Domingo sold theirs for only P12/kg to P13/kg. A farmer in Kabulihan, General Natividad meanwhile sold his produce for P16/kg.

Other production costs

Fertilizers, Ka Carling noted, are not the only expenses they shoulder in planting rice. For this season, he bought Triple 2 rice seedlings for P1,200 per sack. A hectare of land requires two sacks of seedlings, which means he spent P4,800 for his rice land.

From preparing to sowing the seedlings, he then spent P2,800 to P3,000 per hectare for tractor services. In this case, the farmer does not pay it immediately because the same services should be hired during the harvest season.

After using a tractor machine, a farmer spends another P3,000 for hand tractor services to better prepare the farmland. Once the seedlings are ready, a farmer pays P2,400 per hectare for uprooting them and preparing for transplanting.

In planting rice, Ka Carling said a farmer then pays farm workers more or less P6,000 per hectare. During the harvest season, a farmer has to pay for a reaper harvester.

“For reaper-harvester machine services, the rate is 10 cavans per 100 cavans of produce. The owner of the machine is the one to give a sack to the barangay, ” he said in Filipino.

The barangay stocks rice supplies for families in need of aid and relief goods, especially during the pandemic.

The machine owner also gives another sack to a middleman, so that’s one for the barangay, one for the agent, and the remaining ones are left for the harvester operator, he added.

Add to this the payment for workers who will haul or transport the sacks of unhusked rice from the farm. Ka Carling said the current rate is P30 per sack.

In 2019, according to data from the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), the cost of producing palay during the wet season cropping amounted to P11.38 per kilogram.

In 2021, rice farmers organization Samahang Industriya ng Agrikultura (SINAG) said the cost of production climbed up to P15 per kilogram.

Rice tariffication law

The 65-year-old farmer also lamented the impact of the Rice Tariffication Law. The rice imports, he said, caused the prices of palay to drop since its passage.

Republic Act No. 11203 essentially lifted all existing quantitative restrictions on importing rice “such as import quotas prohibitions, imposed on agricultural products, and replacing these restrictions with tariffs.”

The law also created a Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (RCEF), otherwise referred to as “Rice Fund” which consists of an annual appropriation of P10 billion for six years after the enactment of the law in 2019. A Rice Fund, under this law, was supposed to be allocated for machineries and equipment, rice seed development, expanded credit assistance, and other extension services.

Ka Carling said the assistance came late.

He said they were told the tariffs collected through the law would be given back to them. He assumed this may be the rice seeds that were distributed to them, but not on time.

“Tapos na ang taniman, saka lang magbigay ng punla. Maitatanim pa ba ‘yung punla na iyon? Nakapunla na ‘yung mga tao, saka lang ibigay. Hindi na magagamit sa dapat paggamitan ‘yun. Sa pataba naman, wala rin sa panahon,” Ka Carling added.

(They give seedlings to us at a time when the planting season is over. Can we still plant those? Most farmers here have already finished preparing their lands and seedlings, and that’s just when they give them. We can no longer use that. Even fertilizers do not come on time.)

Farmers were then left with no choice but to sell the seeds or use them as food for livestock.

“‘Yung iba ginagawa na lang ibinebenta na lang. ‘Yung iba naman pinapagiling na lang at pinapakain sa mga hayop. Kasi sa susunod na punlaan, ‘pag ma-over na sa pagka-stock, hindi na pupuwede itanim,” he said.

(Some just sell it while others process it as food for their livestock. Because if it gets stocked for too long, it can no longer be used for planting.)

These impacts were echoed by Leopoldo Alcantara, a farmer from Guimba, Nueva Ecija, who said that gone are the days when farmers in the rice granary of the Philippines were able to sell their palay for above P20 per kilo.

“Noon, nagkakaroon kami ng presyong P22, P23 (per kilo). Nabawasan ng P10 sa ganitong panahon,” Leopoldo lamented.

(Pre-pandemic, we were able to sell our produce for P22 to P23 per kilo. Now it decreased by P10.)

Leopoldo said he refuses to believe the Philippines needs rice imports to feed its people.

“Sinasabi nila na kulang daw ‘yung supply ng bigas. Bilang isang magsasaka, hindi kami naniniwala na kukulangin ‘yung produkto nating magsasaka. Ngayon sinasabi nila na para (mapunan) ang pagkukulang nag-aangkat sila,” he told Rappler.

(They say we do not have sufficient supply of rice. But as a farmer, we do not believe that our produce is not enough. Now they say we need to import rice just to fill in the gaps.)

A rice self-sufficient nation

Former agriculture secretary Manny Piñol, under whose term the RTL was passed, said the law “is now making life difficult for the Filipino rice farmers.”

This comes after he recalled that the country’s economic managers ridiculed his projection early in 2016 when he said that the country can achieve rice sufficiency. The formula was simple, he said.

The government has to provide additional small water irrigation systems; give farmers access to hybrid and high-yielding seeds; allow farmers access to low-cost and sufficient farm inputs; provide farmers village-level farm dryers and basic production machinery; and provide access to low-interest production loans.

“I never realized that the economic managers had a different agenda and that was to open the Philippine Rice Market to unimpeded rice importation, reportedly as part of some international loan concessions,” he said in a social media post on Thursday, September 23.

Piñol also said the “rice shortage” in 2017 was artificial, which happened after the National Food Authority Council prevented the National Food Authority from importing buffer stocks for the lean months of 2018.

Piñol said he continued his advocacy, nevertheless. He cited the case of Ilocano farmers in Matalam, North Cotabato, who were able to increase their harvest from one to three times a year – dramatically increasing their yield from 3 metric tons to 21 metric tons – after receiving a solar-powered irrigation system, a small tractor rotavator, and a combine-harvester.

“So, there, I have proven my case. I feel vindicated, of course, but I regret we wasted five years,” he said.

Lack of government support

Guimba farmers urged incumbent and future local and national leaders to provide genuine support for Filipino farmers “who feed the nation.”

“’Yan ang malaking dagok sa mga magsasaka: ‘yung walang kontrol sa pag-angkat sa ibang bansa,” said Leopoldo. (That’s the major blow against farmers: uncontrolled rice importation.)

“Sa ngayon, maririnig mo ba na ang gobyerno ay may pagmamahal sa mga magsasaka? Parang wala eh. Mahal nila ‘yung mga magsasaka, madali nilang paikutin ‘yung mga magsasaka, dahil nandiyan ‘yung boto ng mga magsasaka na kailangan ng mga pulitikong matataas. ‘Yan sana ang dapat nilang pag-aralan naman dahil kawawa talaga ang mga magsasaka,” he added.

(At present, do we hear anything from the government expressing concern for farmers? I think there’s none. They only care for farmers because politicians need their votes. That’s something the government should study because farmers are really in a sorry condition.)

Article and Images Sources: Rappler.com – https://www.rappler.com/nation/break-even-good-news-rice-granary-philippines-struggles-covid-19-pandemic